The variant is simple: instead of attempting to roll the 'to-hit' number on 2d6 for each individual unit attacking in a combat, players consult a table that converts the 'to-hit' numbers of each attacker into fractions of 36. These fractions are then added together and a hit registered each time a whole number is reached (ie, 36 points). Left over fractions are then reconverted to a 'to-hit' number, against which 2d6 are rolled to see whether an extra hit is scored.

In practice, what this means is that players can predict the likely course of the action with far more certainty than usual, and in keeping with Patrick's philosophy, the game becomes less dependent on dice and more dependent on player choices.

The battle we chose for our refight was Pharsalus as it is fairly well documented and thus relatively easy to refer back to for testing purposes. The dice gods gave me command of the forces of the ever magnanimous Gaius Julius Caesar, while Patrick took those of that opportunistic demagogue [lately turned establishment] Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus...

|

| Caesar listening to Cato the Younger. (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

| Pompeius listening to Cato the Younger. (Wikimedia Commons) |

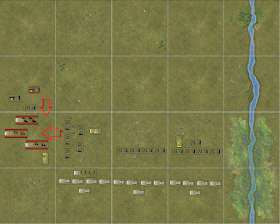

Historical deployment (turn 1).

Pompeius (bottom of screen) begins by advancing the cavalry on the left and deploying his average legionaries in line. Caesar sends forward his own cavalry and positions his veteran legionaries across the three central zones, though with more weight on his right. Marcus Antonius commands the left wing.

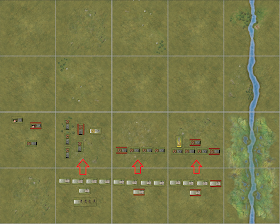

Turn 2 (Pompeius' move).

Pompeius orders the cavalry to attack on his left. One of Caesar's units is spent; the other is lucky to escape the same fate. Pompeius himself leads reinforcements to join the cavalry. The skirmishers reintegrate with the infantry on the left, but the legionaries stay put, reluctant to advance and give Caesar's men the first strike.

Turn 2 (Caesar's move).

Unbeknownst to Pompeius*, Caesar declares a flip-flop, and reverses the turn order. In preparation for the imminent attack he reinforces his cavalry wing and advances the infantry into contact. His right concentrates on the cavalry, intending to see off the immediate threat before turning on the infantry.

*As a nice touch, it turned out that Patrick had forgotten Caesar's ability to do this, so he was indeed caught out by this unexpected manoeuvre!

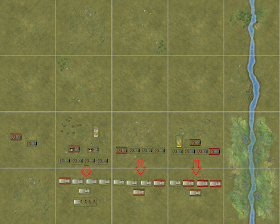

Turn 3 (Caesar's move).

Caesar now uses the flip-flop to attack Pompeius' cavalry. By leading off with his own zone he is able to inflict three hits, which results in all of the cavalry units being left spent. Caesar's cavalry wing now piles in and shatters the lead unit, and this carries the rest of the cavalry off the field in flight. Pompeius himself makes for the safety of the camp, taking him out of the battle.

The legions crash together, with Marcus Antonius' wing launching a determined attack at some cost to the tenth legion.

Turn 3 (Pompeius' move).

Pompeius' infantry resist strongly, putting pressure on along the line. They are unable to take advantage of Caesar's distraction on the left (the carry-over roll was not successful), but they have numbers on their side and from here on it will be a grinding fight.

Turn 4 (Caesar's move).

Caesar swings his right about to face the infantry of the Pompeian left, with modest success. He pulls the cavalry in behind him to provide extra strike power and sends Crastinus' surviving friends to the far right with instructions to await orders for an outflanking move.

Elsewhere the grind continues, with Marcus Antonius, pressing the attack strongly, in inspirational form on the left.

Turn 4 (Pompeius' move).

Pompeius' men maintain the line doggedly, with their effectiveness giving both Caesar and Marcus Antonius immediate cause for concern. If the Optimates can maintain their strength and enthusiasm for the battle they could yet fight Caesar to a standstill.

Turn 5 (Caesar's move).

With the battle at its crisis point, Marcus Antonius rises to the challenge, urging his veterans to remember their courage and drive off the enemy. They respond by shattering an enemy unit. Are the Pompeians about to lose heart?

Caesar signals for the right wing to advance and outflank the Pompiean left.

Turn 5 (Pompeius' move).

The left attacks vigorously (it gets five attacks due to the presence of the outflanking force) but fate does not smile kindly upon the men, and they cannot find a break in the line.

Turn 6 (Caesar's move).

Marcus Antonius' men shatter one unit and need a carry-over roll of 5 to shatter another. An 8 is scored, so the second unit also shatters, reducing the morale of the entire army down to zero. The other troops in the zone run, as do the light infantry from the left.

Finally, the combined attacks on the Pompiean left drive the rest of the army off the field. The day belongs to Caesar, but it is Marcus Antonius to whom the laurels must go!

The final points tally sees Pompeius claim a well-deserved handicap victory by 97 points to 91, on the back of his having spent 13 units' worth of Caesar's valuable veterans.

So how did it go?

The result was quite similar to the historical result. Pompey stayed on his baseline and did not fight for the centre, which gave Caesar a morale advantage he did in fact claim to have had historically. This meant that it was easier for Caesar to force the rout of the entire army. While this was advantagous in VP terms (for Pompey did not lose so many units shattered), if the Pompeians has stayed on field longer they may have been able to score some shatters of their own, thereby increasing the margin of game victory.

And the averaging system?

This seemed to work pretty well for a first outing, but it is not without its quirks. Double hits are out of the game, meaning that light infantry has lost some of its character, and the precisely calculable nature of the combat table meant that there was a real hesitancy to undertake certain moves, an example being Caesar's reluctance to make an outflanking move due to the fact that it would give Pompeius' men an extra attack on the left, with the increased likelihood of a carry-over hit being scored having the potential to quickly exhaust Caesar's limited manpower resources.

But we'll need more tests to see what effect on player decisions the increased predictability will have.

But we'll need more tests to see what effect on player decisions the increased predictability will have.

We played this game with set command and morale rolls, so adding variation there might be a good way to introduce more uncertainty but without altering the attrition rate significantly.

There are some small changes and at least one more test planned, so we'll see how it goes. I think Patrick has done a good job, and as far as having the variant do what it is intended to do is concerned, he seems to be on the right track.

|

| Some years later... |

Cle: How fascinating, Antonius! I never tire of that story. Would you please tell me that bit about the CRT again?

Thanks, a very enjoyabls AAR, Aaron.

ReplyDeleteSimon

Many thanks, Simon. It's very nice to hear from you again. I hope all is going well!

ReplyDeleteBeautiful post! :)

ReplyDeleteThanks, Piero!

ReplyDeleteNice, and like the 'before' and 'after' photos at each end. I still have my doubts about Patrick's system, but that discusion is for another place.

ReplyDeleteThanks Andrew, and I appreciate your dropping by!

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure that the constant mutual attrition model is correct either, but it has been a good experience trying it out, and so far has proved a useful tool for reconstructing 'average' results.

We're about to do another test, this time introducing Patrick's variant rally rules, so I'll report back on that at some stage as well.

Cheers!