I'm currently putting together a research article (hopefully for Slingshot) and Lost Battles scenario for a not-so-well-covered battle from the 2nd Punic War and did a quick play test last night.

As it turned out, quick was the operative word!

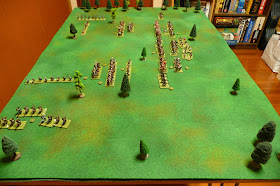

This is a summary of the action. Note that the text is positioned below the relevant photograph.

Rome (on the left hand side of the table) deploys first, utilising a light infantry screen with heavy cavalry in support. Carthage responds by advancing its heavy cavalry in the centre and putting the Numidians on the flanks.

Rome gets first attack, and makes it count. She scores five hits, curdling the cream of the enemy cavalry straight out of the pail (I know; sorry for inflicting that one on you...).

Carthage in return manages only two hits. A low command roll prevents her from advancing the Numidian cavalry as speedily as would normally be desirable.

Rome continues to attack with devastating effect - one unit is shattered in the Carthaginian centre and those around it panic and flee. Rome has a breakthrough almost immediately! Elsewhere, the Carthaginians lose another unit on the left and the velites score a hit on the advancing light cavalry.

The Carthaginian cavalry begins to inflict some damage of its own, shattering a unit of velites on the Roman left and leaving most of the forward Roman units spent. She also gets the Numidians in position to envelop the Roman line.

The Romans appear exhausted by their breakthrough: they are unable to press the attack with any success at all this turn. The enemy commander manages to rally the only hit that is made and the Carthaginians can scarcely believe their good fortune. Moloch will no doubt be expecting due reward!

Carthage seizes the initiative and with it the advantage: her attack panics and scatters the Roman left just as the Numidians get in behind the Roman right.

The enemy numbers are starting to tell but Rome is not quite done yet. The cavalry of the right break through as well, driving off the Carthaginian left centre. Rome now controls the middle of the field, but the enemy commander is still alive and the Numidians are marauding with intent...

The Carthaginian commander now turns inwards to attack the Roman centre: he shatters a fourth Roman unit, and this, combined with a low morale roll, is enough to see the Roman survivors head for the safety of the camp while they still may.

Points tally:

Carthage shattered 3 light infantry units and a heavy cavalry unit for 24 points. She routed 6 heavy cavalry units and a light infantry unit for another 28 points. She forced the withdrawal of 2 more light infantry units, another 2 heavy cavalry units and the commander for a further 15 points.

Carthage then scored 67 points.

Rome shattered 3 heavy cavalry and 1 light cavalry unit for 24 points. She routed 4 heavy cavalry and 2 light cavalry units for a further 24 points. An enemy light cavalry unit was left spent, for another 3 points.

Rome scored 51 points and gained another 30 on handicap. The total of 81 is enough to give her the game victory.

Pages

▼

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Useful readings on the Hannibalic War

I'm doing a spot of research at the moment and have been giving the Second Punic War collection a bit of a time off the shelf. This is a list of what I've been using.

Please feel free to comment, and extra points are yours to command if you add in your own favourite sources for this period!

Hannibal's War by J.F. Lazenby. Excellent overview. Gives his sources and is not controversial. As far as I'm concerned is still the starting point for all investigations.

The War With Hannibal by Titus Livius. An excerpt from Livy's history. Essential, along with Polybius.

A History of the Roman World by H.H. Scullard. Good source looking at the wider context. Not as in- depth for this period as Lazenby, but worth checking to see what he has to say.

Roman Warfare by Adrian Goldsworthy. General coverage of the Roman approach to war. Summarises rather than presents. Has decent suggestions for further reading.

The Fall of Carthage by Adrian Goldsworthy. A good single book history of the three wars against Carthage. Very readable and includes copious notes. This and Lazenby are the two books most focussed on the Hannibalic period.

In the Name of Rome by Adrian Goldsworthy. Again, another readable book from Goldsworthy. Gives military biographies of quintessential Roman generals. Includes Fabius, Marcellus and Scipio Africanus from our period.

Cavalry Operations in the Ancient World by Robert E. Gaebel. A very interesting look at the development of cavalry warfare. Not especially necessary for the Second Punic War however.

Warfare in Antiquity by Hans Delbruck. Dated but still formidable. Spends a lot of his time savaging contemporaries and pointing out flaws or inconsistencies in the ancient evidence. Still, worth referencing as a strong, opinionated and perhaps instructive voice.

Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars by Duncan Head (drawings by Ian Heath). The ancient wargamer's bible.

Soldiers and Ghosts by J.E. Lendon. Quite an unusual treatment. Contends that warfare in a Greek and Roman context was an emulation of heroic myth or legend and an embodiment of cultural attitudes. I don't agree with everything he says but it's a brilliant and imaginative re-interpretation. Again, not essential reading as far as the Hannibalic period goes, but not off-topic either.

Lost Battles by Philip Sabin. Gives good overviews of the main clashes including troop numbers, terrain, and general course of the fighting. Also touches on some of the scholarly debates around the battles themselves.

I've been using some online sources as well - Polybius especially (and wikipedia when I'm cheating) - but it's nice to have hard copies in front of you. So much time is spent on a computer these days it's almost relaxing to go back to pen and paper for a spell!

Anyway, that's me done. Feel free to comment and add to the list. It's always good to be introduced to new books on this topic and on ancient warfare in general.

Please feel free to comment, and extra points are yours to command if you add in your own favourite sources for this period!

Hannibal's War by J.F. Lazenby. Excellent overview. Gives his sources and is not controversial. As far as I'm concerned is still the starting point for all investigations.

The War With Hannibal by Titus Livius. An excerpt from Livy's history. Essential, along with Polybius.

A History of the Roman World by H.H. Scullard. Good source looking at the wider context. Not as in- depth for this period as Lazenby, but worth checking to see what he has to say.

Roman Warfare by Adrian Goldsworthy. General coverage of the Roman approach to war. Summarises rather than presents. Has decent suggestions for further reading.

The Fall of Carthage by Adrian Goldsworthy. A good single book history of the three wars against Carthage. Very readable and includes copious notes. This and Lazenby are the two books most focussed on the Hannibalic period.

In the Name of Rome by Adrian Goldsworthy. Again, another readable book from Goldsworthy. Gives military biographies of quintessential Roman generals. Includes Fabius, Marcellus and Scipio Africanus from our period.

Cavalry Operations in the Ancient World by Robert E. Gaebel. A very interesting look at the development of cavalry warfare. Not especially necessary for the Second Punic War however.

Warfare in Antiquity by Hans Delbruck. Dated but still formidable. Spends a lot of his time savaging contemporaries and pointing out flaws or inconsistencies in the ancient evidence. Still, worth referencing as a strong, opinionated and perhaps instructive voice.

Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars by Duncan Head (drawings by Ian Heath). The ancient wargamer's bible.

Soldiers and Ghosts by J.E. Lendon. Quite an unusual treatment. Contends that warfare in a Greek and Roman context was an emulation of heroic myth or legend and an embodiment of cultural attitudes. I don't agree with everything he says but it's a brilliant and imaginative re-interpretation. Again, not essential reading as far as the Hannibalic period goes, but not off-topic either.

Lost Battles by Philip Sabin. Gives good overviews of the main clashes including troop numbers, terrain, and general course of the fighting. Also touches on some of the scholarly debates around the battles themselves.

I've been using some online sources as well - Polybius especially (and wikipedia when I'm cheating) - but it's nice to have hard copies in front of you. So much time is spent on a computer these days it's almost relaxing to go back to pen and paper for a spell!

Anyway, that's me done. Feel free to comment and add to the list. It's always good to be introduced to new books on this topic and on ancient warfare in general.

Thursday, June 12, 2014

Review of Labyrinth: the War on Terror 2001-?

I was lucky enough to be able to take advantage of GMT Games' recent 50% off sale and, having watched a few documentaries on the Royal Marines in Afghanistan, thought I'd like to try a game from the COIN series just to see what the system is like (and what the fuss is about). A Distant Plain was sold out, so I went for Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-? as it seemed to be in the same ball park.

To be fair and open, historical moderns is not really my thing. I enjoy hypothetical Cold-War-goes-hot stuff, but actual recent or ongoing conflicts feel raw to me and I find it a little uncomfortable thinking about gaming them.

It was therefore with slight wariness that I approached Labyrinth, which takes as its subject the post-9/11 war on terrorism. Please keep this in mind while reading this review.

Anyway, let's take a look at the game itself.

Anyway, let's take a look at the game itself.

The first thing you notice is that it is played on a beautiful, hard-mounted map. The featured countries are classed as either Muslim or non-Muslim, and they are tracked differently depending upon which category they fall into. Muslim countries have governance (Islamic rule, poor, fair or good) and stance vis-a-vis the US (ally, neutral or adversary) noted, while non-Muslim countries have a counter for posture (hard/soft), indicating whether or not they support the use of force against extremism.

Countries may also harbour terrorist cells, US troops, or a combination of the two.

|

| The game board, clearly enough... |

To win the game the US must keep its prestige high and use 'war of ideas' plays to ensure good governance in Muslim states. The Jihadist player must try to keep funding levels high, reduce US prestige - and therefore its ability to influence other nations - and look to foment Islamic rule in Muslim states or set off a WMD in the US itself.

The game revolves around card play, with each card being able to be used as an event or as an operations play. Sometimes, if the card is an enemy event, you might have to play it as both an operation for you and an event for the enemy, so how best to use the cards dominates decision-making.

US operations options include 'war of ideas' in which the US gets, under certain conditions, to roll to improve the governance or stance of a Muslim country. The lower US prestige, and the greater the difference between US posture (hard/soft) and the posture of the rest of the non-Muslim world, the smaller the chance of this roll succeeding.

The US may also attempt a 'war of ideas' operation to get a non-Muslim country to change its posture from hard to soft, or vice versa. Again, this depends on a die roll.

The US may opt to use an operations turn to disrupt terrorist cells, foil a terrorist plot, or deploy troops. Troops can generally only be deployed to allied Muslim nations, but the US does have a game-changer option: regime change, whereby the US may order regime change against any country under Islamic rule. This immediately changes the governance of the country to poor ally and brings a significant troop commitment while the US attempts, over time, to end Jihadist resistance and bring the governance level up to good.

The US player has a sort of firefighter role - he or she must look to keep prestige high, maintain alliances, disrupt terrorist cells, use force where needed, promote good governance in Muslim nations, uncover plots and, above all, prevent a WMD attack on US soil.

Naturally enough, the Jihadist player also has a number of options. These include being able to recruit terrorist cells in certain areas, send cells to other nations, set up plots and use either of two different types of jihad to disrupt governance in Muslim countries in an attempt to bring these states closer to or under Islamic rule.

The US is powerful, but can't do everything at once, so the Jihadist player must try to stretch the US as much as possible, lower its prestige, and make it difficult to respond to every threat.

The game also includes solitaire rules (a key feature for me - most of my play is solo), which see the Jihadist side played by an automated system. Apparently there are plans to bring out rules to automate the US side which will be made available through a future edition of GMT Games's house magazine, C3i.

We've been talking so far about operations, but as one of the prime uses of cards is for events, I'd better mention them as well. In fact, it's with these events that things get really interesting (and tricky). There are 120 event cards, and over a turn each player must use the eight or nine cards in his or her hand judiciously. Some events are more useful than others at certain times, or require conditions to be right, or are at their best used before or after the play of other particular events. Learning the card deck is probably the most important thing if you want to become a competitive player of these types of games.

Now, in most card-driven games, this is where things start to get less appealing for me. I don't really want to have to learn a card deck and associated optimal plays to be able to do all right in a game. If I want to play cards, I'll play a traditional card game. But the way that Labyrinth approaches card play seems fresh and does not result in the sense of frustration that I've had with some other games in the genre. I've been happy just to play through the cards as they come, hand by hand, and haven't felt that I'm missing anything on a macro level by not knowing optimal plays.

That said, I'm still ambivalent about the game itself. As I said before, I'm not very comfortable with modern conflicts - especially ongoing ones - and that is a major difficulty for me. It's nothing I didn't know already however, so I'm not going to hold that against the game.

I find that the game mechanisms are clever, but the treatment (necessarily, of course) is at times simplistic and does not go into deeper causes or ramifications, and therefore any understanding that may be generated is, to me, undercut by the feeling that the game is presented from the US side of the divide. As a way to understand a US narrative of an approach to fighting extremism it may be a reasonable approximation, but as a way to come to grips with the wider nuances I think it is of less value.

As an example, we have the Predator card:

This is a positive card for the US if played as an event. However, what it does not show is the anecdotal real-world negative effect that the use of drones has on perceptions of US moral authority and is one example of how the game misses the double-edged nature of much of the goings on in the war against extremism. That it misses this is due I think to a) it being designed within a particular paradigm, b) us finding that the real world has outgrown the game, and c) the unavoidable imperative to simplify things to fit within a playable game system.

So, points in favour: it's challenging; it has asymmetrical sides; there is plenty of room for player skill; and it is beautifully produced. Points not in favour: the simplifications reduce the value it might have in terms of understanding the conflict; it attempts to quantify a lot of unknowns, some of which have been or will inevitably be overtaken by events; and there is a sense that it is not distanced enough from its subject to be able to see causes, events, and results entirely objectively, even though the intent to be objective is there.

In conclusion I would say that it is an attractive introduction to modern card-driven game systems, has historical interest as a snapshot of 2011 US insider thinking around the war on Islamic extremism, and is likely to prove to be very interesting as a game. But if you are looking for a definitive treatment of this murky ongoing conflict you will have to wait a bit longer.

The game revolves around card play, with each card being able to be used as an event or as an operations play. Sometimes, if the card is an enemy event, you might have to play it as both an operation for you and an event for the enemy, so how best to use the cards dominates decision-making.

US operations options include 'war of ideas' in which the US gets, under certain conditions, to roll to improve the governance or stance of a Muslim country. The lower US prestige, and the greater the difference between US posture (hard/soft) and the posture of the rest of the non-Muslim world, the smaller the chance of this roll succeeding.

The US may also attempt a 'war of ideas' operation to get a non-Muslim country to change its posture from hard to soft, or vice versa. Again, this depends on a die roll.

The US may opt to use an operations turn to disrupt terrorist cells, foil a terrorist plot, or deploy troops. Troops can generally only be deployed to allied Muslim nations, but the US does have a game-changer option: regime change, whereby the US may order regime change against any country under Islamic rule. This immediately changes the governance of the country to poor ally and brings a significant troop commitment while the US attempts, over time, to end Jihadist resistance and bring the governance level up to good.

The US player has a sort of firefighter role - he or she must look to keep prestige high, maintain alliances, disrupt terrorist cells, use force where needed, promote good governance in Muslim nations, uncover plots and, above all, prevent a WMD attack on US soil.

Naturally enough, the Jihadist player also has a number of options. These include being able to recruit terrorist cells in certain areas, send cells to other nations, set up plots and use either of two different types of jihad to disrupt governance in Muslim countries in an attempt to bring these states closer to or under Islamic rule.

The US is powerful, but can't do everything at once, so the Jihadist player must try to stretch the US as much as possible, lower its prestige, and make it difficult to respond to every threat.

The game also includes solitaire rules (a key feature for me - most of my play is solo), which see the Jihadist side played by an automated system. Apparently there are plans to bring out rules to automate the US side which will be made available through a future edition of GMT Games's house magazine, C3i.

We've been talking so far about operations, but as one of the prime uses of cards is for events, I'd better mention them as well. In fact, it's with these events that things get really interesting (and tricky). There are 120 event cards, and over a turn each player must use the eight or nine cards in his or her hand judiciously. Some events are more useful than others at certain times, or require conditions to be right, or are at their best used before or after the play of other particular events. Learning the card deck is probably the most important thing if you want to become a competitive player of these types of games.

|

| Sample cards showing events, who they favour, and operations value (OpV # in box) |

Now, in most card-driven games, this is where things start to get less appealing for me. I don't really want to have to learn a card deck and associated optimal plays to be able to do all right in a game. If I want to play cards, I'll play a traditional card game. But the way that Labyrinth approaches card play seems fresh and does not result in the sense of frustration that I've had with some other games in the genre. I've been happy just to play through the cards as they come, hand by hand, and haven't felt that I'm missing anything on a macro level by not knowing optimal plays.

That said, I'm still ambivalent about the game itself. As I said before, I'm not very comfortable with modern conflicts - especially ongoing ones - and that is a major difficulty for me. It's nothing I didn't know already however, so I'm not going to hold that against the game.

I find that the game mechanisms are clever, but the treatment (necessarily, of course) is at times simplistic and does not go into deeper causes or ramifications, and therefore any understanding that may be generated is, to me, undercut by the feeling that the game is presented from the US side of the divide. As a way to understand a US narrative of an approach to fighting extremism it may be a reasonable approximation, but as a way to come to grips with the wider nuances I think it is of less value.

As an example, we have the Predator card:

This is a positive card for the US if played as an event. However, what it does not show is the anecdotal real-world negative effect that the use of drones has on perceptions of US moral authority and is one example of how the game misses the double-edged nature of much of the goings on in the war against extremism. That it misses this is due I think to a) it being designed within a particular paradigm, b) us finding that the real world has outgrown the game, and c) the unavoidable imperative to simplify things to fit within a playable game system.

So, points in favour: it's challenging; it has asymmetrical sides; there is plenty of room for player skill; and it is beautifully produced. Points not in favour: the simplifications reduce the value it might have in terms of understanding the conflict; it attempts to quantify a lot of unknowns, some of which have been or will inevitably be overtaken by events; and there is a sense that it is not distanced enough from its subject to be able to see causes, events, and results entirely objectively, even though the intent to be objective is there.

In conclusion I would say that it is an attractive introduction to modern card-driven game systems, has historical interest as a snapshot of 2011 US insider thinking around the war on Islamic extremism, and is likely to prove to be very interesting as a game. But if you are looking for a definitive treatment of this murky ongoing conflict you will have to wait a bit longer.

Friday, June 6, 2014

Poets who were also wargamers

In this piece we shall look at the work of a number of poets who were closet wargamers. Quite why they kept their interest in wargaming secret we can only speculate, but the evidence of their love of the little tin men is there in the texts for all to see.

We start with a close reading of Good-by by the great American Transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882).

Good-by, proud world, I'm going home,

Thou'rt not my friend, and I'm not thine;

Long through thy weary crowds I roam;

A river-ark on the ocean brine,

Long I've been tossed like the driven foam,

But now, proud world, I'm going home.

This stanza finds the poet dissatisfied after a long day at a wargames show. Sadly, it is now impossible to be sure which show it was, but it is likely to have been put on by prototypical French Symbolists. The essential facts are clear nevertheless: our poet has copped a hiding in the participation game, the overpriced pastry he got for lunch was stale, and he missed out on those nicely painted Gordon Highlanders at the bring-and-buy after Edgar Allen Poe edged in front of him, the magpie.

The remainder of the poem is a passive-aggressive wish-fulfillment fantasy in which the speaker ruminates on a final return to nature after the crowds of sweaty bodies, the dubious air-conditioning and the unfair victory conditions.

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) also fell hard for the table, with the scene of his epiphany powerfully related in As I Ponder'd in Silence.

As I ponder’d in silence,

Returning upon my poems, considering, lingering long,

A Phantom arose before me, with distrustful aspect,

Terrible in beauty, age, and power,

The genius of poets of old lands,

As to me directing like flame its eyes,

With finger pointing to many immortal songs,

And menacing voice, What singest thou? it said;

Know’st thou not, there is but one theme for ever-enduring bards?

And that is the theme of War, the fortune of battles,

The making of perfect soldiers?

Whitman's later career was characterised by extreme hobby confusion and the sense that he could only hint publicly at what he privately felt, yet in this brave, unguarded verse the Phantom represents what is surely Whitman's own True Voice. To paraphase, only tabletop battles, the writing of after action reports and the casting of accurately proportioned, historically authentic but not overly bendable tin soldiers are things truly worthy of a poet's attention.

Wargaming - this whisper roars - is the true Stuff of Life.

With that we turn east to the olympian Irishman William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) and his apocalyptic vision, The Second Coming.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

In an age-old lament prefiguring the great Games Workshop debates by nearly a century, we here find the poet bemoaning a rules change which he clearly felt would have dire repercussions for future tournament play, and probably even for isolated house-ruling cliques. Not only are the rule writers out of touch with the reality of the games table, he charges, but they empower the tournament gamer at the expense of the genuine history enthusiast.

The end results of this particular revision are not recorded, but a reading of the second verse does not give the impression that the cracks could be easily papered over. Exactly who the rough beast of the second stanza is is a contentious question, but Aleister Crowley is surely a prime candidate.

T.S. Eliot (1888-1965) is another famous - if dry - poet who quaffed from the wargaming bucket. Initially a wargame skeptic, his conversion to Anglicanism allowed him to see wargaming in a new light, as an exercise in futile world-creation. This was fertile soil indeed for an inveterate pessimist.

We meet him, appropriately enough, in The Waste Land (V - What the Thunder Said).

Here is no water but only rock

Rock and no water and the sandy road

The road winding above among the mountains

Which are mountains of rock without water

If there were water we should stop and drink

Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

If there were only water amongst the rock

Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

There is not even silence in the mountains

But dry sterile thunder without rain

There is not even solitude in the mountains

But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

From doors of mudcracked houses

Here we have a verbatim record of Eliot's narrator in the role of gamesmaster, describing in visceral detail the terrain features of his J.G. Frazer derived "kill the king, devour the queen, spear the children under this red rock" skirmish scenario. Regard his repetitive use of negative forms: "no", "without", "neither" and "not", which combine to lend a mythic quality to the task. As an aside, we have good reason to believe that at this time the players may well have been Gertrude Stein and the enigmatic Alice.

Although publicly austere, W.H. Auden's (1907-1973) work suggests that he was more fantastical in regards to his private wargaming tastes. Witness his August 1968:

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for Man,

But one prize is beyond his reach,

The Ogre cannot master Speech:

About a subjugated plain,

Among its desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips,

While drivel gushes from his lips.

The scene presents itself larger than life. His Men of Eastfold overmatched with a min-maxed 8th edition Ogre army, the narrator is forced to fall back upon racist stereotyping to disguise the hurt and humiliation that attends defeat. It is easier to insult the Ogre than it is to admit his own shortcomings as a commander.

Auden once again shows himself the master of brevity and spareness when presenting underlying psychological truth.

Space precludes us continuing further, but this short study alone makes it abundantly clear that the extensive cabal of wargaming poets has had great influence, dominating both the cannon and the canon.

Notes:

Looking into a writer's life for clues about the possible meaning of his work is a practice now much frowned upon, yet research has thrown up what I consider to be relevant biographical information, so I shall include it, for those who may be curious.

- Ralph "Wargame" Emerson was a secret devotee of such enthusiasm that he wanted to convert an isolated shack in the woods into a storage / gaming room and call it "Walled In". Thoreau thought he was taking the mickey and forced him to settle for an attic, like everyone else.

- "Whiff" Whitman was so famous for fluffing his artillery rolls that people would stand on desks and recite "Oh Captain, My Captain" if he ever hit. This was the inspiration behind the memorable moment in the later film, Dead Poets Society, featuring "Rob 'em" Williams, who is as well known for stealing battles as he is scenes.

- William Butler "Bleats" was infamous for complaining about his poor dice (game room tradition has it he is a distant relation of the author of this piece).

- "B.S." Eliot had a reputation for constant, critical table talk. During one of Hemingway's famous WWI Italian Front game days Eliot told Papa that it was ludicrous for the ambulance corps to be represented on-table in 1/72 scale. Hemingway whacked him one and dared him to say it again. The situation would have turned ugly if F. Scott Fitzgerald had not chosen that moment to rise from the floor and shout "absinthe makes the heart grow fonder."

- "Warhammer" Auden, it is said, as well as an eye for the fantastic, possessed a penchant for lost causes, always preferring to take the side of the underdog. Funeral Blues, for instance, is rumoured to have been inspired by a singularly traumatic refight of Thermopylae.

We start with a close reading of Good-by by the great American Transcendentalist, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882).

|

| Before the show |

Good-by, proud world, I'm going home,

Thou'rt not my friend, and I'm not thine;

Long through thy weary crowds I roam;

A river-ark on the ocean brine,

Long I've been tossed like the driven foam,

But now, proud world, I'm going home.

This stanza finds the poet dissatisfied after a long day at a wargames show. Sadly, it is now impossible to be sure which show it was, but it is likely to have been put on by prototypical French Symbolists. The essential facts are clear nevertheless: our poet has copped a hiding in the participation game, the overpriced pastry he got for lunch was stale, and he missed out on those nicely painted Gordon Highlanders at the bring-and-buy after Edgar Allen Poe edged in front of him, the magpie.

The remainder of the poem is a passive-aggressive wish-fulfillment fantasy in which the speaker ruminates on a final return to nature after the crowds of sweaty bodies, the dubious air-conditioning and the unfair victory conditions.

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) also fell hard for the table, with the scene of his epiphany powerfully related in As I Ponder'd in Silence.

As I ponder’d in silence,

Returning upon my poems, considering, lingering long,

A Phantom arose before me, with distrustful aspect,

Terrible in beauty, age, and power,

The genius of poets of old lands,

As to me directing like flame its eyes,

With finger pointing to many immortal songs,

And menacing voice, What singest thou? it said;

Know’st thou not, there is but one theme for ever-enduring bards?

And that is the theme of War, the fortune of battles,

The making of perfect soldiers?

|

| Wargamer and Poet |

Wargaming - this whisper roars - is the true Stuff of Life.

With that we turn east to the olympian Irishman William Butler Yeats (1865-1939) and his apocalyptic vision, The Second Coming.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

|

| The slayer from Sligo |

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

In an age-old lament prefiguring the great Games Workshop debates by nearly a century, we here find the poet bemoaning a rules change which he clearly felt would have dire repercussions for future tournament play, and probably even for isolated house-ruling cliques. Not only are the rule writers out of touch with the reality of the games table, he charges, but they empower the tournament gamer at the expense of the genuine history enthusiast.

The end results of this particular revision are not recorded, but a reading of the second verse does not give the impression that the cracks could be easily papered over. Exactly who the rough beast of the second stanza is is a contentious question, but Aleister Crowley is surely a prime candidate.

|

| With WRG 1st Edition |

We meet him, appropriately enough, in The Waste Land (V - What the Thunder Said).

Here is no water but only rock

Rock and no water and the sandy road

The road winding above among the mountains

Which are mountains of rock without water

If there were water we should stop and drink

Amongst the rock one cannot stop or think

Sweat is dry and feet are in the sand

If there were only water amongst the rock

Dead mountain mouth of carious teeth that cannot spit

Here one can neither stand nor lie nor sit

There is not even silence in the mountains

But dry sterile thunder without rain

There is not even solitude in the mountains

But red sullen faces sneer and snarl

From doors of mudcracked houses

Here we have a verbatim record of Eliot's narrator in the role of gamesmaster, describing in visceral detail the terrain features of his J.G. Frazer derived "kill the king, devour the queen, spear the children under this red rock" skirmish scenario. Regard his repetitive use of negative forms: "no", "without", "neither" and "not", which combine to lend a mythic quality to the task. As an aside, we have good reason to believe that at this time the players may well have been Gertrude Stein and the enigmatic Alice.

Although publicly austere, W.H. Auden's (1907-1973) work suggests that he was more fantastical in regards to his private wargaming tastes. Witness his August 1968:

|

| Orcs or Goblins? |

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for Man,

But one prize is beyond his reach,

The Ogre cannot master Speech:

About a subjugated plain,

Among its desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips,

While drivel gushes from his lips.

The scene presents itself larger than life. His Men of Eastfold overmatched with a min-maxed 8th edition Ogre army, the narrator is forced to fall back upon racist stereotyping to disguise the hurt and humiliation that attends defeat. It is easier to insult the Ogre than it is to admit his own shortcomings as a commander.

Auden once again shows himself the master of brevity and spareness when presenting underlying psychological truth.

Space precludes us continuing further, but this short study alone makes it abundantly clear that the extensive cabal of wargaming poets has had great influence, dominating both the cannon and the canon.

Notes:

Looking into a writer's life for clues about the possible meaning of his work is a practice now much frowned upon, yet research has thrown up what I consider to be relevant biographical information, so I shall include it, for those who may be curious.

- Ralph "Wargame" Emerson was a secret devotee of such enthusiasm that he wanted to convert an isolated shack in the woods into a storage / gaming room and call it "Walled In". Thoreau thought he was taking the mickey and forced him to settle for an attic, like everyone else.

- "Whiff" Whitman was so famous for fluffing his artillery rolls that people would stand on desks and recite "Oh Captain, My Captain" if he ever hit. This was the inspiration behind the memorable moment in the later film, Dead Poets Society, featuring "Rob 'em" Williams, who is as well known for stealing battles as he is scenes.

- William Butler "Bleats" was infamous for complaining about his poor dice (game room tradition has it he is a distant relation of the author of this piece).

- "B.S." Eliot had a reputation for constant, critical table talk. During one of Hemingway's famous WWI Italian Front game days Eliot told Papa that it was ludicrous for the ambulance corps to be represented on-table in 1/72 scale. Hemingway whacked him one and dared him to say it again. The situation would have turned ugly if F. Scott Fitzgerald had not chosen that moment to rise from the floor and shout "absinthe makes the heart grow fonder."

- "Warhammer" Auden, it is said, as well as an eye for the fantastic, possessed a penchant for lost causes, always preferring to take the side of the underdog. Funeral Blues, for instance, is rumoured to have been inspired by a singularly traumatic refight of Thermopylae.